Faced with an unstable security condition and an influx of refugees, the Regreening Africa programme is having to rethink its work.

By Susan Chomba, May Muthuri and Hamed Constantin

Just two years into the implementation of the Reversing Land Degradation in Africa by Scaling-up Evergreen Agriculture (Regreening Africa) project, a major surge in insecurity in Niger is threatening the process and reversing the gains made in restoring degraded lands.

Niger is a transit country. It has experienced an influx of refugees seeking asylum from internal and external extremist groups. At the dawn of 2020, the situation worsened through a series of attacks by jihadists on military positions of territorial protection. The attacks led to more movement of refugees and deepened the humanitarian crisis.

The longstanding conflict perpetuated by Jihadists and affiliated groups has displaced more than 350 households (2520 people), hailing from several villages (some of which Regreening Africa is active in), including more than 1150 children between the ages of 0–17 years. According to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees, the numbers are staggering, with a 196,717 internally displaced persons countrywide.

16,000 refugees seek shelter following clashes in north-east Nigeria. Photo: UNHCR

16,000 refugees seek shelter following clashes in north-east Nigeria. Photo: UNHCR

The farmer-managed natural regeneration areas that had been protected by local communities, as well as planted trees, are being destroyed as internally displaced people search for material for makeshift shelters and firewood for food preparation and warmth at night. New areas are being cleared for farming. Social conflicts are simmering between longer-term residents (in French, the ‘autochthon’) and new occupants as people compete for scarce resources. According to a recent United States Agency for International Development report, approximately 1.4 million people in Niger are now facing crisis, or worse, levels of acute food insecurity as a result. The Agency projects the number may increase to more than 1.9 million during the forthcoming rainy season, June–August 2020.

The unprecedented wave of insecurity and violent attacks has reduced mobility of Regreening Africa project staff to the sites, thus, hampering the implementation and monitoring process. ‘The current situation has displaced quite a number of project beneficiaries in the affected villages,’ said Moctar Abdou Mahamadou, Technical Assistant in Field Opperations from CARE Niger. ‘Their involvement in project activities is also diminishing, especially women and youth, as they are more vulnerable to insecurity. Households are mostly focusing on survival. It’s unfortunate we, too, as project staff can’t do much as we are not allowed to move around.’

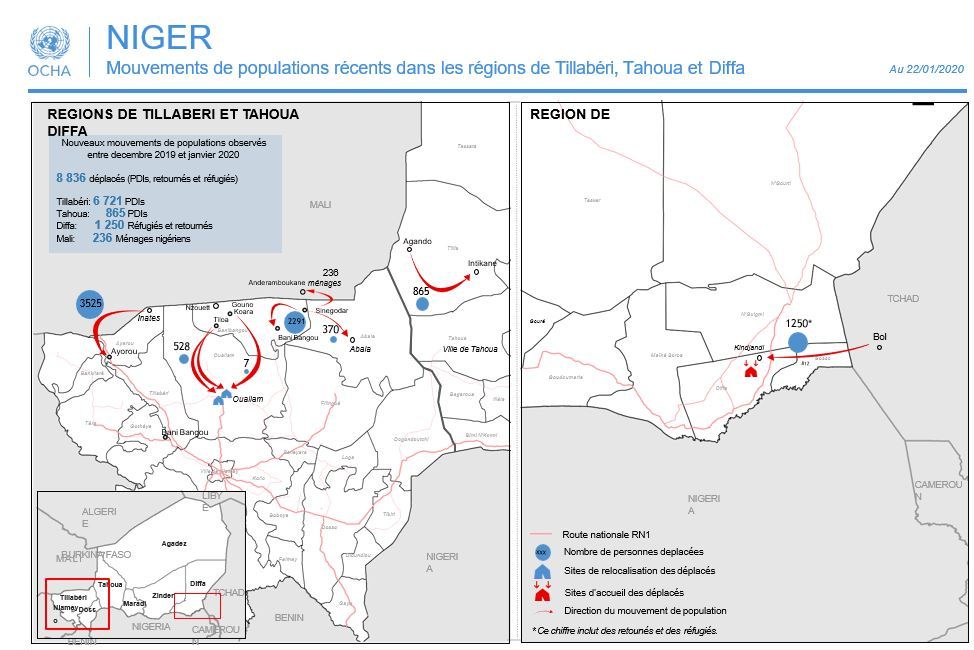

Map showing refugee movement to Tillabéri, Tahoua and Diffa regions in January 2020. Source United Nations office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Niger

The same applies to the farmers who are the project beneficiaries, as explained by Abdoul Aziz Hamadou, a leading farmer from Toloboye Koira Tengui Village in Ouallam Commune.

‘Since the advent of insecurity in the area,’ said Hamadou, ‘I am afraid to go to my farm located a couple of kilometres from my village. Even if I do so, it’s out of deep fear as the slightest noise, especially one of a motorbike approaching, sends me into sheer frenzy as my life is at stake. The situation is quite unfortunate as my daily routine to cut down crop residues, pruning, clearing weeds and maintaining tree nursery cannot be done properly or with the perfection it deserves. The rains are approaching, and I may not enjoy the work of my hands. This will cost me greatly.’

Regreening Africa has set ambitious targets to reverse degradation on 40,000 hectares and positively impact the livelihoods of 90,000 households. This European Union-funded programme commenced activities in late 2017 in Hamdallaye, Ouallam and Simiri communes. Over time, World Agroforestry (ICRAF), in partnership with World Vision Niger and CARE Niger, has supported farmers’ groups, government authorities and other stakeholders to be part of the restoration agenda.

ICRAF, World Vision and CARE project staff taking soil samples for analysis of soil organic carbon and other land degradation indicators. Photo: World Agroforestry

ICRAF, World Vision and CARE project staff taking soil samples for analysis of soil organic carbon and other land degradation indicators. Photo: World Agroforestry

ICRAF has been a key player in working together with CARE and World Vision and farmers’ groups to identify suitable restoration practices, as well as tree species, for different agro-ecological niches; assessing soil health quality through the Land Degradation Surveillance Framework; and monitoring restoration through ground surveys, mobile-phone technologies and satellite imagery. All of which has been paving the way for sustainable restoration.

Farmers’ fields and community centres have been buzzing with restoration and livelihoods’ activities, such as development of tree-based value chains, training sessions on tree-nursery establishment and management, and expanding the scale of soil and water conservation techniques, such as ‘zai pits’ and ‘half-moons’. Project beneficiaries were bound to reap both short- and long-term benefits through the spread of sustainable agricultural practices.

‘I was really excited to perfect the art of digging water retention structures, such as zai pits and half-moons, and learning how to practice Assisted Natural Regeneration (RNA),’ said Hamadou. ‘With relevant trainings the past year, I have been faithfully carrying out these activities on a 0.5 hectare section on my farm that I considered highly degraded. The turnaround in yield is amazing as I now harvest 34 bunches of millet and six bunches of sorghum, giving a yield of 1120 kilograms per hectare, which used to be 500 kilograms per hectare. This additional yield gives me great satisfaction and definitely convinces me of the effectiveness of the activities I practice on my farm out of the rainy season. Having perfected my newly acquired skills, I have expanded regreening activities to other parts of my farm, solely, without help of the technical staff.’

Niger has long been known as the wonder child of successful restoration efforts following a resurgence of assisted natural regeneration over an area estimated at 5 million hectares of once degraded land, mainly in Zinder and Maradi regions, in the 1970s and 1980s. The concept of being a ‘clean farmer’, which means clearing trees on one’s farm, was slowly fading away, paving the way to protection of 200 million trees, according to the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100). In return, this translated to an increase of 100 kg per hectare, per year, in cereal production, boosting annual yield by 500,000 tonnes, benefiting 2.5 million people.

It is also one of the poorest countries in the world, an estimated population of 21.6 million and one of the highest birth rates: on average, a woman in Niger gives birth to 8 children. For most, what comes to mind when they hear of Niger is desert-like fields with barely suitable land for farming, hot temperatures, frequent droughts decimating livestock and people, and widespread poverty. But hope in restoration of Niger’s land was beginning to take shape, as highlighted in ‘the quiet revolution’ of Maradi and Zinder.

Unfortunately, that great restoration story does not seem to have been replicated across the country, where farmers continued with the default practices of a ‘clean farmer’. Hence, the need for more concerted efforts to restore degraded lands in other regions. A lot remains to be done, even by 2030, if we are to move closer to the 3.2 million hectares that Niger promised to restore under AFR100 and the Bonn Challenge.

What does this mean for Regreening Africa and others who have been playing their part in restoration? Plans are underway to relocate to different sites less likely to be affected by these issues and also to continue engaging through local governments to monitor what can be done to keep the gains in the insecure zones. Commencing activities in new sites is definitely a major step back for the project because the entire process of community mobilization and trust building and training begins all over again. But given the urgency and necessity to restore degraded landscapes this would be a worthwhile venture. The question is, how sustainable will these efforts be?

Learning from other areas, Regreening Africa will also take such as risks and design interventions for both refugee and resident communities.

‘In refugee crises, it’s crucial to maintain environment and trees,’ said Cathy Watson, chief of ICRAF’s programme development unit. ‘Done right from the start, refugee crises can be managed to minimize damage to the environment and to the refugees themselves and their host communities. Severe damage can be averted if environmental thinking becomes part of humanitarian responses.’

About Regreening Africa

Regreening Africa is an ambitious five-year project funded by the European Union that seeks to reverse land degradation among 500,000 households, and across 1 million hectares in eight countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. By incorporating trees into croplands, communal lands and pastoral areas, regreening efforts make it possible to reclaim Africa’s degraded landscapes.

This story was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Regreening Africa and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.