By Joan Baxter. December 21, 1018

Trees are important sources of income for many women in the drylands of West Africa, yet women often have little say in decisions about how land and trees are managed or how household income is used. This story reports on a series of community workshops organised by the West Africa Forest-Farm Interface (WAFFI) project, which set out to explore gender inequity and what might be done to change things for the better.

Community members listened with rapt attention as research findings about differences in sources of household income and decision-making powers amongst men and women were presented in graphs drawn on large sheets of paper. There was a lot of interesting material to digest and to discuss. The results showed large variations in access to assets and resources amongst men and women, and some strong imbalances in how decisions are made within households.

Gloria Adeyiga (left), Ana Maria Paez (centre) and Emilie Smith Dumont present research findings to the community of Gwenia, northern Ghana. Photo: World Agroforestry

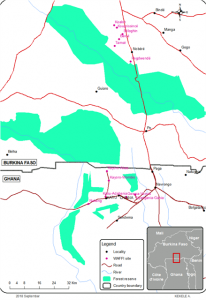

At one workshop, fifteen women and eight men from the village of Gwenia in Kassena-Nankana West District in Ghana’s Upper East Region, ranging in age from late teens to early 80s, gathered in the women’s community centre. Facilitating the activities were Gloria Adeyiga of the Forestry Research Institute of Ghana, Ana Maria Paez Valencia, World Agroforestry (ICRAF) gender specialist, and Emilie Smith Dumont, who has coordinated the WAFFI project in northern Ghana and southern Burkina Faso for ICRAF.

This is a region where diminishing tree resources, land degradation and climate change have increased women’s vulnerability, while restrictive socio-cultural norms offer limited opportunities for women to participate in, and benefit from, landscape restoration or agroforestry initiatives. ICRAF scientists think that addressing gender inequity is a key to unlocking women’s potential to make livelihoods and landscapes more productive and resilient.

This is a region where diminishing tree resources, land degradation and climate change have increased women’s vulnerability, while restrictive socio-cultural norms offer limited opportunities for women to participate in, and benefit from, landscape restoration or agroforestry initiatives. ICRAF scientists think that addressing gender inequity is a key to unlocking women’s potential to make livelihoods and landscapes more productive and resilient.

In Gwenia, Adeyiga and Smith Dumont presented findings from their innovative participatory research that explored wealth variations within, and across, communities. Interviews had been conducted simultaneously with the male family head and one adult female in 36 households.

Tree dependence is high in the region, so income from tree resources was of particular interest. The data showed that while women are involved in all farm and livestock activities, they depend heavily on trees for cash income that they can control; a quarter of women bring in more than 40% of household income from tree products.

Shea butter. Photo: World Agroforestry

The main tree products in the area are shea nuts (Vitellaria paradoxa), charcoal, firewood, baobab fruit [Adansonia digitata], shea butter processed from the nuts , and tamarind. For women, sheanuts are extremely important. More than half of the households surveyed receive income from the nuts, nearly all of it controlled by women. In households where income comes from firewood and shea butter, most of the income is controlled by women. Baobab and tamarind (Tamarindus indica) are also income sources exclusively for women. But, where charcoal contributes income, as it does in more than 30% of households, women receive only a very small share of it. Of immediate concern is that shea trees are now the most common source of wood for charcoal making, so a key resource for women is being diminished by the male-dominated charcoal trade.

While tree resources in the area are decreasing because of growing pressure on them for charcoal, clearing for agricultural land, and uncontrolled bush fires, men are becoming increasingly interested in shea, as global markets expand for the precious butter and nuts, used as a cocoa-butter substitute in food, and also in cosmetic products.

When it comes to farm size and access to land, there are also marked gender differences. On average, women cultivate less than half a hectare and men more than four times that much. In 40% of the households, women have no access to land to cultivate themselves. Men make the decisions about how much land is allocated to women.

There are variations in cash income between men and women and from one household to the next. On average, almost half of household income comes from crops, mostly from men’s farming, and a third from livestock. But this is not always the case: in some households all of the crop income comes from women. Importantly, as Smith Dumont and Adeyiga reported to the workshop in Gwenia, their research showed that men make most of the decisions on how household income is used.

At the end of the presentation, community members were asked if they were surprised by the gender imbalances the data revealed. One participant, Stephen Adayira, said he was surprised to see the amount of income that women contributed to the household, and that women did so much to support the household.

‘Men thought they were doing that,’ he said.

Transforming gender norms

This was not the only time during the workshop that there was surprise expressed about the extent of gender inequity in the community.

Participants in Gwenia discuss where to place photos illustrating household duties based on gender norms in the community. Photo: World Agroforestry

In another exercise, participants were given photographs illustrating various household and farm duties, from ploughing fields, to washing clothes or sweeping a compound, to processing seeds from Parkia biglobosatrees to make the condiment, ‘dawadawa’. They then allocated the photographs to either male, mainly male, mainly female or exclusively female categories that were marked on a sheet of paper, based on who generally performed the tasks.

The placement of the photos revealed that women had far more household responsibilities than men. Asked whether they thought this gender imbalance was creating problems, some female participants responded that it was indeed a problem, and that women ‘age faster’ and ‘get sick more often’ than men.

Participants agreed that there could be more balance in household duties and that a few of the all-female chores — such as washing up and cooking, for example — could readily be shared by men.

The village-level gender workshop was the first of two held under the WAFFI project, the second being in the community of Séloghin in the Nobéré Department of southern Burkina Faso. Both revealed similar gender imbalances and responses from male and female participants. But there was also agreement that things have changed since the time of their grandparents. Men have been assuming a few more previously female responsibilities, women have taken up more farming duties and now have more freedom to speak their minds in public than in the past.

The workshops also included role plays, where women dressed up as men and assumed their roles in making decisions on tree-planting, use of income and in household chores, while men acted as women. These allowed both men and women to challenge gender norms and provoke a great deal of laughter and discussion in both communities. ICRAF scientists think that building these activities into development programmes might lead men and women to change their behaviour.

Some of the remarks were very telling.

In Séloghin, one young man admitted that playing a woman for him was ‘tiring’ and that he felt ‘shamed’ by the need to listen to a domineering husband.

After the gender role play in Séloghin, ICRAF’s Emilie Smith Dumont (right) enjoyed some humorous moments with Bibata Ouedrago (left) still wearing a man’s ‘smock’. Photo: World Agroforestry

Bibata Ouedraogo said she enjoyed playing a man.

‘It is very interesting being head of the household,’ she said. ‘Even if you don’t tell the truth, you have the power.’

‘This will make us change our daily lives,’ commented another woman.

Can gender transformative research lead to better restoration outcomes?

The findings from the WAFFI project, including during these participatory activities, suggest that efforts aimed at land restoration and increased resilience in Sahelian countries will be more successful if they can do something to change gender norms that restrict women’s participation in decision making and undervalue their roles in the landscape and in livelihood systems. This mirrors recent work in East Africa, showing the importance of differences in how women and men view degradation status across their landscapes and the appropriateness of different restoration options.

‘I think these workshops initiated a dialogue in the communities around how gender norms and roles, which usually go unquestioned, may be limiting people from making the best use of the resources they have available,’ says ICRAF’s Ana Maria Paez Valencia. ‘This dialogue helps them realize these norms can change, to improve their well-being and resilience.’

‘Tackling harmful gender stereotypes and gaps cannot be considered as an accessory to technical interventions, it is a critical requirement to achieve sustainable outcomes,’ says Emilie Smith Dumont.

Gloria Adeyiga was so struck by the potential for transformative change that she now wants to focus her PhD research on the extent to which including gender transformative activities in scaling up agroforestry in the Regreening Africa programme can change outcomes, in terms of what tree species are planted and retained in fields, how much income is generated and how it is used to improve the livelihoods of men, women and children in northern Ghana. This is made possible by support from the Livelihood Systemsflagship of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry.

Edward Akunyagra of World Vision, who co-ordinates the regreening programme in Ghana said that the WAFFI research has highlighted the need to ‘develop approaches that integrate gender analysis and participatory methods in ways that support community dialogues around sensitive issues like gender inequity, leading to transformative outcomes and impact’.

For more information, please contact Ana Maria Paez Valencia, ICRAF, Gender, Regreening Africa: a.paez-valencia@cgiar.org

Discover more about gender and land restoration from the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry

Read how men and women perceive land degradation status and restoration options differently in Ethiopia: Crossland M, Winowiecki LA, Pagella T, Hadgu K, Sinclair FL. 2018. Implications of variation in local perception of degradation and restoration processes for implementing land degradation neutrality. Environmental Development 28:42–54.

Read how gender influences knowledge about indicators of soil quality and soil management practices along a land-degradation gradient in Rwanda: Kuria AW, Barrios E, Pagella T, Muthuri CW, Mukuralinda A, Sinclair FL. 2018. Farmers’ knowledge of soil quality indicators along a land degradation gradient in Rwanda. Geoderma Regional e00199.

The West Africa Forest-Farm Interface (WAFFI) is led by the Center for International Forestry Research in collaboration with ICRAF and Tree Aid with support from the International Fund for Agricultural Development and the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. WAFFI aims to identify practices and policy actions that improve the income and food security of smallholders in Burkina Faso and Ghana through integrated forest and tree management systems that are environmentally sound and socially equitable.

This story was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the Regreening Africa project and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.